I love trains. Always have. They must have figured in my childhood, except that in those days, in impoverished postwar Britain, there was not much long-distance travel. So I’m guessing the love affair began in 1953, when my parents put me on to the Royal Scotsman steam train, to travel overnight alone from Birmingham to Edinburgh.

Just last week we took the Scotrail train up from Dunkeld to Inverness for the day. We wanted to see the last of the snowfall on the Cairngorms, and so we did…

As I write in my book Chasing Shooting Stars:

Was it a sign of the times that they could be so trusting? Maybe they assumed me a well-seasoned traveller since I went to school daily on the bus. For they simply asked a couple with a dog – an old smelly spaniel with long, ragged ears – to keep an eye on me. I remember feeling sick with excitement (not fear). And going to sleep with my head on the dog’s soft but solid rump.

At some point during the night I wake to find the compartment full of soldiers, drinking, smoking, playing cards and singing. I think, this is the life, and with a sense of pure contentment, return to my slumbers.

On a train just like this…

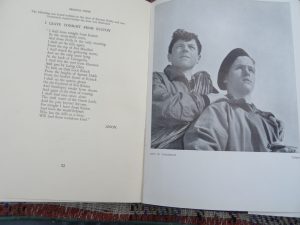

I was met in Edinburgh by my father’s elder sister, Catharine, who drove me to her home in Inverness. A former PE teacher, and a cricketer who played both at County level and for England, she was working for the Scottish Council for Outdoor Education, and had just published a book.

Published in 1951, with her own photographs, and the poem below (found on a bothy door, author unknown) that echoes my own love of the journey from Euston to the Highlands…

These MEN OF TOMORROW are now my age, if not older…MEN OF NOW, or even MEN OF YESTERYEAR….

I was thinking about this trip not so long ago, travelling down to London from Edinburgh on a Virgin train, for my first-cousin Genevieve’s cremation and the gathering at her home afterwards.

Gen’s mother had died in 1953, which is apparently why I was sent away, in complete ignorance, so that my father could help handle the immediate family crisis. His younger sister Elizabeth (Betty) had died in childbirth, and there was a inconsolable three-year-old (Gen), her distraught father, and a newborn to care and plan for.

My parents were also, I suspect, trying to protect me… protect me from death. But I think they were wrong. Maybe they thought me too young and sensitive to deal with it. In this I know they were wrong. Maybe the reaction was rooted in the Victorian mores in which they had grown up. Who knows now, for they are both passed on, and now that my own mother’s younger sister is no longer with me, there is no-one to ask.

It is an odd feeling. There is no-one now alive on either side, my mother’s or father’s, who can share my childhood. My memories are mine alone.

My first up close and personal experience of death was at age 21, when my father died; he was 51. His body lay in our front room for several days before the funeral, with my mother wailing as if the world had come to an end. Her own had, apparently, which is why she spent the next fifty years as a “professional’ widow. So sad, such a waste.

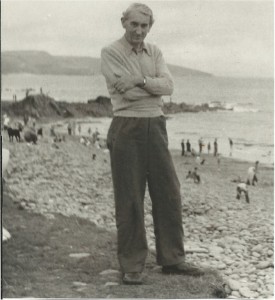

Samuel Robert Loader (1911-1962). Here not long before his death, old before his time… He always loved water, the sea.

What do I remember of his death?

It was late November, and icy cold. A corpse that my mother insisted I kiss. The look of him, and a sickly sweet smell that was nothing remotely to do with the father I loved. Also a sense of rage, that he would leave us all in such

a mess. We had parted badly, he and I, and all I could think was, Did you die because you thought that my leaving home meant I didn’t love you, didn’t care? How foolish was that!

I have no memory of any wake, either before or after.

I still miss him.

In Japan I was witness to three Japanese Buddhist-style funerals. I say Buddhist-style because Japan has a habit of taking on cultural imports from abroad and after some home-grown tweaking, making them their own.

The crematorium: imagine a long bare room with ovens down one side. Being (I have recently learned from DNA testing) that I am one per cent Western European Jewish, they still give me the shivers.

The body is wheeled in on a trolley, the priest recites sutras (prayers), the family members say goodbye, the trolley is pushed into the oven, the doors clank shut, and everyone goes off to a side room for green tea and chat.

Around an hour later, the family is summoned to return. The oven doors are opened and the trolley is wheeled out, revealing what is left of the corpse: ash and bones. Relatives then pick out the bones with chopsticks and – to one side, in a semblance of privacy – place them inside an urn in logical order from feet to skull cap.

The first time I experienced this, I thought I was going to faint. But then I thought, hold on: this is something to really think about, consider…

By the third funeral I was as pragmatic as the rest. Saying goodbye to a corpse, treating remains in this way, is simply a ritual of respect. It has nothing to do with the ‘person’ (personae) or their life essence, which (to my way of thinking) has long gone.

I have had many discussions and arguments on the subject of funerals, in particular in relation to the open coffin. In Japan, this is normal at the wake, or otsuya (lit, ‘all through the night’) on the evening before a cremation. Once again, a ritual that initially seemed alien and distasteful, frightening even, became one that I can honestly say I came to love, in part because of the love displayed towards memory and the physical body of the deceased, which at this stage were intertwined.

I first experienced an open coffin at a friend’s funeral – one I had forgotten about, so four – but in this instance I attended only the otsuya, and not the kasou (lit. ‘funeral by fire’, or cremation) that followed on.

As a single mother, Tomiko had left her daughter an orphan, and it was immensely moving to see how she said goodbye to her mother: placing Tomiko’s make-up bag in the coffin, together with her favourite operatic CD, and a photograph of them together. She then invited everyone to surround her mother’s face with roses, while an Italian aria of great beauty filled the space left behind, and our hearts.

If only I had grown up with such personalized celebrations! Instead I was left baffled and dismayed by the body of the man who had in part created me, lying skeletal, yellow, cold and decaying, with the house full of whispers and denial. Where had my father gone? He was not there for sure. For the first time it made me consider the mystery of the separation of the physical and spiritual once the energetic life force/soul/atman has left the shell, but there was no-one to discuss it with.

My cousin Gen – her poor body ravaged by MS (multiple schlerosis) — was carried into the crematorium in a beautiful willow-woven casket. A simple bouquet of white flowers lay on top. There was music – a string quartet, a song from a group of her son’s friends (all professional singers), a Shakespearian sonnet, a tribute from her best friend from long-gone school days. Then – Gen having gone ahead to leave behind years of pain and suffering – her body was returned to dust and ashes, and physically she was gone.

And yet, her smile is still with me… it feels as if she’s not so far away. Maybe just across the mountains to the north?

Maybe I ought to take a train.

Not a romantic but slow and essentially filthy coal-fuelled train from the 1950s.

Not a narrow Virgin train in which there is hardly room to swing a cat, the toilets are stuffed, and the tea tastes of dusty tea bags.

Not the stunning new state-of-the art shinkansen bullet train that we rode on in Japan last year between Akita and Tokyo; glory hallelujah for just about everything: comfort, speed, bento box, lunches, green tea.

Not the stunning new state-of-the art shinkansen bullet train that we rode on in Japan last year between Akita and Tokyo; glory hallelujah for just about everything: comfort, speed, bento box, lunches, green tea.

And not the next one either… just another one, soon .